Student debt insolvencies on the rise

Student debt in Canada is in a crisis. We say this because we see the negative consequences of more and more young people taking on student loans, in higher amounts. In 2018, student debt contributed to more than 1 in 6 (17.6%) insolvencies in Ontario1, a record rate since we began our study nine years ago. Extrapolate this Canada-wide, and that means that roughly 22,000 ex-students filed insolvency in 2018 to deal with their student debt.

That may not seem like a lot but put in perspective with the number of student loan borrowers in relation to the overall population, the young age of these borrowers, and the relative health of the economy in recent years, and it is an epidemic.

In this report, we take an in-depth look at the student loan crisis in Canada and the profile of the average insolvent student debtor. We explore who are defaulting on their student loan debt and why they are filing insolvency at an increasing rate.

Note: In Canada, consumer insolvencies include both personal bankruptcy and a consumer proposal, both student debt forgiveness options under the Bankruptcy & Insolvency Act.

Student debt in Canada

It’s hard to get a handle on the amount of student debt outstanding in Canada. As of the 2016/2017 school year, Canada Student Loans (CSL) was administering a portfolio2 of $18.2 billion dollars in loans to more than 1.7 million borrowers.

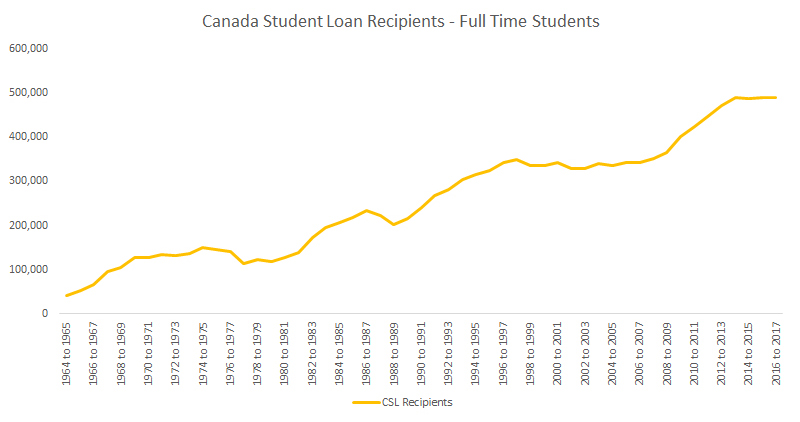

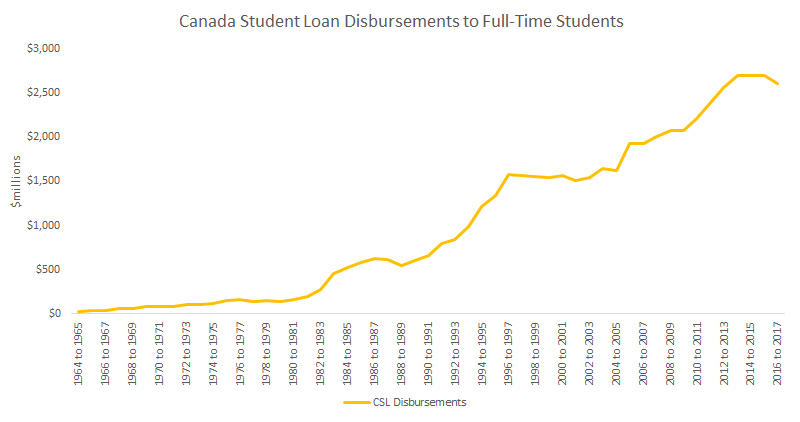

In 2016/2017, Canada Student Loans disbursed $2.6 billion in loans to 490,401 students. While loan disbursements dipped in the most recent year, over the past ten years, CSL has disbursed 47% more in loans to 31% more students than in the previous ten years.

However, on top of the federal government guaranteed loan program, graduates are also financing their studies through additional provincial student loans and private loans.

For students in full-time study in participating jurisdictions, approximately 60% of their CSL assessed financial need is funded by the Government of Canada through federal student loans, while the province or territory covers the remaining 40%. How much is in loans, and how much is grants, varies by province based on political objectives. In Ontario in 2017/2018 for example, OSAP funded3 almost $1.7 billion in financial aid, only $200 million of which was repayable loans, with the remainder being grants. The year before funding of just over $1 billion was split 60% grants and 40% loans.

Private student loans are another matter, no-one reports on how much is out there.

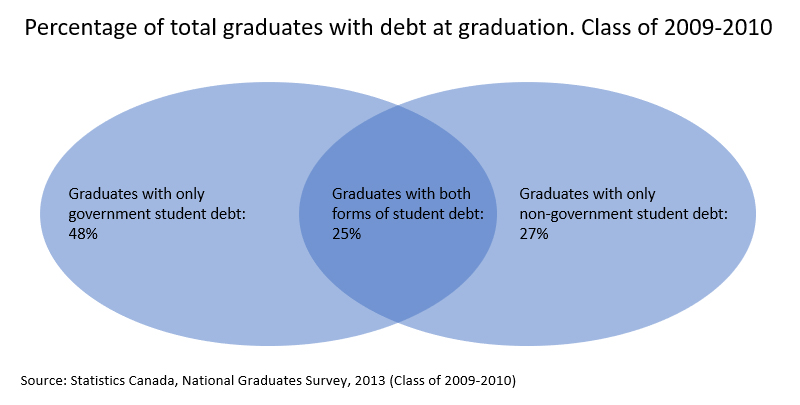

A National Graduates Survey4, conducted by Statistics Canada, revealed that while government loans are the most common source of debt for students, 27% of graduates from the class of 2009-2010 used only non-government loans and 25% relied on both government student debt and non-government debt.

While the average undergraduate completed university with an average debt load of $26,300 in 2010, if students supplemented government student debt with a student credit card, bank loan or student line of credit, their average debt balances upon graduation ballooned to $44,200. That means that the average student using private loans on top of their government-guaranteed loans increased their debt load by 68% through private lenders.

Rising tuition contributing to insolvencies

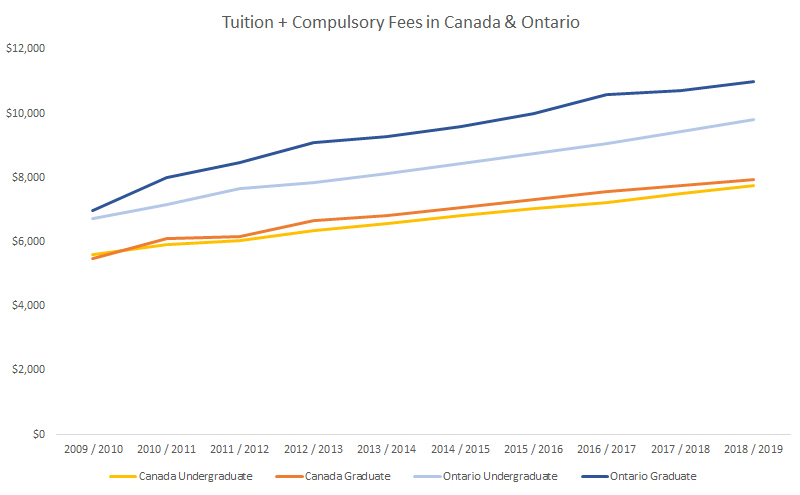

The average undergraduate tuition for a Canadian university5 is now $6,838, and tuition has risen at an annual rate of 3.7% over the past ten years. In Ontario, the average tuition is now $8,838, up an average 4.6% per year over the past ten years. And this is before compulsory fees, costs of books, school supplies, and residence.

Much of the cost of post-secondary education is being financed by student loans. Despite the introduction of the Canada Education Savings Grant program and tax-sheltered RESPs, over 40% of post-secondary students4 finance their education through loans – either government-guaranteed Student Loans or private student debt. This number rises to 50% for university undergraduates.

The issue is that this debt lingers. Only 34% of bachelor graduates had fully paid off their student loans three years after graduation. According to Canada Student Loans, students typically take between nine and 15 years to pay off their student loans in full. But some don’t get there; they declare insolvency (file bankruptcy or make a consumer proposal to creditors) first.

Insolvency being declared much sooner for student debt

Our study shows that tuition hikes are taking their toll on graduates. Higher debt upon graduation is just not sustainable, contributing to many graduates declaring insolvency much earlier than in the past.

Graduates are declaring insolvency much sooner after graduation. The average age of an insolvent student debtor in 2018 was 34.6 compared to 35.7 in 2011 after peaking at 36.1 years in 2012.

While more likely to be in their 30s, three in 10 student debt insolvencies are filed by those aged 18-29 and insolvency among recent graduates is increasing.

To have student debt dissolved in a bankruptcy or consumer proposal, the debtor must have been out of school for at least seven years. This is why the average age of an insolvent debtor is in their mid-30s. They have been out of school, and struggling with repayment, for years. Those who file insolvency with student-related debt still owe an average of $14,729 in student loans representing 32% of all their unsecured debt.

Federal and provincial student loan and grant programs such as OSAP have helped increase enrollment in college and university programs among young Canadians but have also resulted in high post-secondary dropout rates. Historical studies6 by Statistics Canada report a university dropout rate of 16% and a college dropout rate of 25%. Yet these are people who unfortunately still must repay their accumulated student loans, a challenge when they are unable to find suitable employment. Students who did not successfully complete their studies can also have their student debt eliminated, but must wait for their end of study date to be more than seven years before they file their consumer proposal or bankruptcy.

Job-related challenges lead to student debt default

While most student debtors cite poor management of finances as the number one cause of their debt problems, almost one-third (29%) stated that job-related or income issues contributed to their financial problems.

The Canada Student Loans program reported2 a three-year default rate of 9% in 2015-2016. While the default rate is on the decline, this is due primarly to increased use of the Repayment Assistance Program (RAP). CSL reported a total of 305,769 borrowers in the Repayment Assistance Plan, roughly 12% of all direct loan borrowers. What is revealing is that the first year RAP uptake rate has increased over the past five years.

| 2012 to 2013 | 2013 to 2014 | 2014 to 2015 | 2015 to 2016 | 2016 to 2017 | |

| First year RAP uptake rate² | 27% | 28% | 28% | 28% | 31% |

Graduates leaving university often end up working in unpaid internships, part-time positions, and minimum wage jobs. They are increasingly unable to find a stable job with enough income to support both student loan repayment and living expenses. This has contributed to an increase in the percentage of insolvent debtors with unpaid student debt.

If this cycle continues for the minimum seven years after they attended school, and they are still struggling with repayment, a bankruptcy or proposal becomes an alternative for debt relief.

People filing insolvency with student loans are working, in fact, 86% reported being employed. It is the quality of their job and income that is at issue.

The average income for an insolvent student debtor in 2018 was $2,430 – 4.7% below that of the average insolvent debtor without student loans.

Delaying financial obligations and accumulating post-graduate debt

Repaying student debt after graduation takes more than just simple budgeting to pay back this level of loans. The obligation to pay back debt at such an early age creates a cash flow crunch when most are earning a lower than average income. Individuals struggling to repay student debt are unable to build an emergency fund, save for a home, and keep up with student loan payments. Some turn to credit card debt to makes ends meet, and a staggering number of insolvent student debtors use payday loans. In 2018, 45% of student debtors had at least one payday loan at the time of their insolvency.

Payday loans and other revolving debt create a cycle of debt accumulation post-graduation that contributes to their insolvency. In 2018, including student loans, the average insolvent student debtor owed a total of $46,373 in unsecured debt.

It is, however, still student debt that is their primary problem. Student loans account for 32% of their total unsecured balances.

Student debt more of a dilemma for women

Even more concerning, overwhelming student debt is primarily a problem for women. In 2018, 61% of student debtors were women.

This ratio is consistent with Canada Student Loan figures2. In 2016-2017, 61% of grants & loans were distributed to women. CSL also reported that 65% of RAP recipients are female.

The female student debtor (Jane Student) is struggling with more student debt than her male cohort. Jane Student owes an average of $15,171 in student debt, 8.2% more than the average male debtor with student loans, a trend that has occurred consistently since we began our study.

A woman filing insolvency is less likely to be employed at the time of insolvency. In 2018, 83% of female student debtors were employed compared to 90% of male student debtors.

Jane Student struggles to find employment after graduation. The 2009-2010 Graduates Survey reported that while 79.4% of male students were working full-time three years after graduation7, only 71.9% of female graduates were successful at finding a full-time job in that time. Even if she does find employment, Jane Student is much more likely to be out of work for other reasons including maternity leave and childcare, affecting her ability to maintain a stable income source.

It is this susceptibility to having an intermittent income that makes it difficult for Jane Student to keep up with her student loan repayments. Consequently, she has a higher student debt level than do male student debtors.

Women filing insolvency are also much more likely to be single parents than men. Looking at student loan debtors, only 8% of men are single fathers while 34% of women with student debt are single mothers. As a result, Jane Student is struggling to balance both childcare costs and student loan payments on a single income. Compounding this Jane Student has a household income that is 3% below that of male student debtors.

It’s time to eliminate the waiting period

The recent federal budget8 has attempted to make student loans more affordable. While student loan borrowers can choose between a lower floating rate – tied to prime – or a fixed interest rate, 99% of student borrowers choose the variable rate option. The federal government lowered the variable rate to prime and made the initial 6-month payment grace period interest-free on the federal portion of the loan.

In Ontario, interest charges during the grace period on OSAP loans resumed for those graduating as of September 2019 reversing the cost advantage provided by the previous government.

The federal government has instituted a Repayment Assistance Program to help students facing financial hardship with student debt repayment. If the applicant can prove financial hardship, they are entitled to interest relief under Stage 1 for a period of up to 60 months. After that, if still struggling, they may be entitled to both principal and interest relief. Many insolvent student debtors are either participating in this program or do not qualify under the stringent hardship provisions. For many, the postponement of payments does not help when they are also struggling with other debt. And this is contributing the increase in student bankruptcies and consumer proposals in Canada.

When repayment assistance is not enough, student debtors turn to the Bankruptcy & Insolvency Act to resolve their student loan debt; however, they are subject to a waiting period of seven years. Section 178(1) of the act does not release or discharge a debtor from:

any debt or obligation in respect of a loan made under the Canada Student Loans Act, the Canada Student Financial Assistance Act or any enactment of a province that provides for loans or guarantees of loans to students where the date of bankruptcy of the bankrupt occurred

(i) before the date on which the bankrupt ceased to be a full- or part-time student, as the case may be, under the applicable Act or enactment, or

(ii) within seven years after the date on which the bankrupt ceased to be a full- or part-time student;

Simply put – if you have government-guaranteed student loans, you must wait seven years from your last date of study to have these loans discharged in a bankruptcy or consumer proposal.

To complicate matters even more, students can apply for a hardship ruling to have the waiting period reduced to five years if they “experience financial difficulty to such an extent that the bankrupt will be unable to pay the debt”. This requires a court application, with the assistance and expense of a lawyer, and is very difficult to obtain.

Yet if you have private student debt – a bank loan, credit card, or student line of credit – these debts are included in a consumer insolvency and discharged with no waiting period.

It is our opinion that the waiting period for student loan discharge should be eliminated. There is no valid reason to treat government student loans different from private student loans. The intended use for borrowing is the same, no matter the source. These are monies used to pay for the cost of education and living costs. Students do not have to support where they spent the money. OSAP and CLS can be used to pay for tuition, room and board, clothing, food, or any expense while in school not unlike their credit card or line of credit.

If not eliminated entirely, the waiting period should be tied to both the length and benefit of the program they attend and hence expected outcomes. If they drop out of school after one year, they can have any loans discharged after waiting one additional year. If they attend a three-year program, they should be required to wait no more than three years to be eligible for discharge.

It is time we stop saddling an entire generation with debt from which many cannot fully reap any benefit.

Profile of the Average Student Debtor

The average student debtor owes $46,373 in unsecured loans, including $14,729 in student debt. The student debtor is more likely to be female, single, with or without a dependent.

| AVERAGE STUDENT DEBTOR 2018 Update | ||

|---|---|---|

| Personal Information | ||

| Male | 39% | |

| Female | 61% | |

| Average age | 35 | |

| Marital status | ||

| Married or Common-law | 28% | |

| Divorced or Separated | 15% | |

| Widowed | 1% | |

| Single | 56% | |

| Average family size | 2.1 (including debtor) | |

| Likelihood of having dependent | 44% | |

| Average monthly income | $2,430 net of deductions | |

| Total unsecured debt | $46,373 | |

| Unsecured debt-to-income ratio | 159% | |

| Likelihood they own a home | 2% | |

| Average mortgage value | $209,637 | |

| Detailed Information on the amount of average unsecured debt: | ||

| Personal loans | $12,547 | |

| Credit cards | $9,070 | |

| Taxes | $4,130 | |

| Student loans | $14,729 | |

| Other | $5,897 | |

Sources (first instance & charts):

- Hoyes, Michalos Bankruptcy Study

- Canada Student Loans Program statistical review 2016 to 2017 https://www.canada.ca/en/employment-social-development/programs/canada-student-loans-grants/reports/cslp-statistical-2016-2017.html

- Ontario Student Assistance Program annual report http://www.auditor.on.ca/en/content/annualreports/arreports/en18/v1_310en18.pdf

- Graduating in Canada: Profile, Labour Market Outcomes and Student Debt of the Class of 2009-2010 – Revised: Section 4 https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/n1/pub/81-595-m/2014101/section04-eng.htm

- Canadian undergraduate tuition fees by field of study https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/t1/tbl1/en/tv.action?pid=3710000301 and Canadian graduate tuition fees by field of study https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/t1/tbl1/en/tv.action?pid=3710000401

- Participation levels, graduation and dropout rates by December 2005 https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/n1/pub/81-595-m/2008070/figures/6000093-eng.htm

- Percentage of 2009-2010 university graduates working full-time, three years after graduation https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/n1/pub/81-582-x/2015003/tbl/tble2.6-eng.htm

- Federal Budget 2019 https://www.budget.gc.ca/2019/docs/youth-jeunes/youth-jeunes-en.pdf